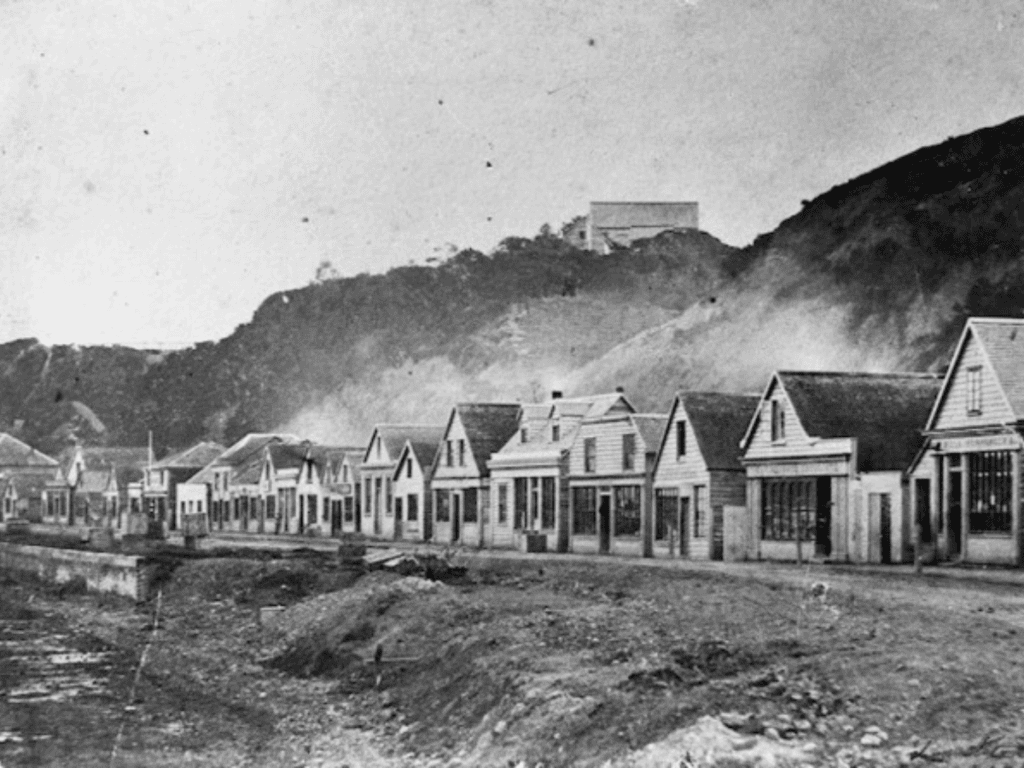

It was an anniversary holiday like no other. It had started out normally with extra visitors in town, festivities to mark the occasion, people visiting friends, playing sport, or watching the boat races and horse races. But by 9.30 pm residents were in a state of shock, their familiar surroundings barely recognisable.

One hundred and seventy years ago, the Wellington anniversary holiday ended abruptly with New Zealand’s biggest earthquake. The magnitude 8.2 Wairarapa Earthquake occurred on 23rd of January 1855 just as parents had put children to bed, and friends and family were winding down after the holiday celebrations.

With shaking that threw people to the ground and made them “feel very sick”1 , the earthquake brought down hillsides, buildings, and the high hopes of colonial settlers in this young town. It raised land out of the sea by over a metre – up to a whopping 6.4 metres near Turakirae Head – and permanently moved Wellington about 16 metres north-eastwards. But that wasn’t all…

“Then came an immense tidal wave, rushing up to the then one-sided street of Lambton Quay, and washing things out of the shops. When it retreated, the whole bay was left high and dry … thousands of dead fish were piled up from Oriental Bay right round to Petone…“2

Less well-known than the earthquake that caused it, the 1855 tsunami is worth remembering. Arriving about 10 minutes after the earthquake as people were still extracting themselves from the rubble of damaged houses and disrupted possessions, fast-moving water was not what they needed. The tsunami was highest on the south coast – in Palliser Bay it swept away a shed that had been 9 metres above sea level. Water flowed over the land between Lyall Bay and Evans bay and inundated Miramar. Inside Wellington Harbour wave heights were lower but the impact was greater because of development on low-lying land.

Earthquakes may be the natural hazard that Wellington is most “famous” for, but the region is also prone to tsunamis. Wherever the seabed can be cut or bent by movement on a fault in a large earthquake or water displaced by landslides, tsunamis are an inevitable consequence. The seafloor of Cook Strait is criss-crossed like a crooked spider web with active faults. Steep-walled canyons provide the perfect breeding ground for submarine landslides.

Thankfully, destructive tsunamis are rare. These hazards are a natural consequence of having a planet with a mobile crust. Readjustments happen over longer timeframes than what we’re used to in our fast-paced human lives, so we need to go back in time. New Zealand’s tsunami database is rife with records of historical tsunamis, but many of these were “alarming disturbances of the sea” rather than widespread flooding of the land by seawater.

Māori oral traditions, archaeological and geological records preserve evidence of larger, older events. Of relevance for Wellington is the discovery of unusual sand and shell layers in the Mataora-Wairau Lagoons and Lake Grassmere that are thought to be the remains of tsunamis triggered by Hikurangi subduction zone earthquakes.

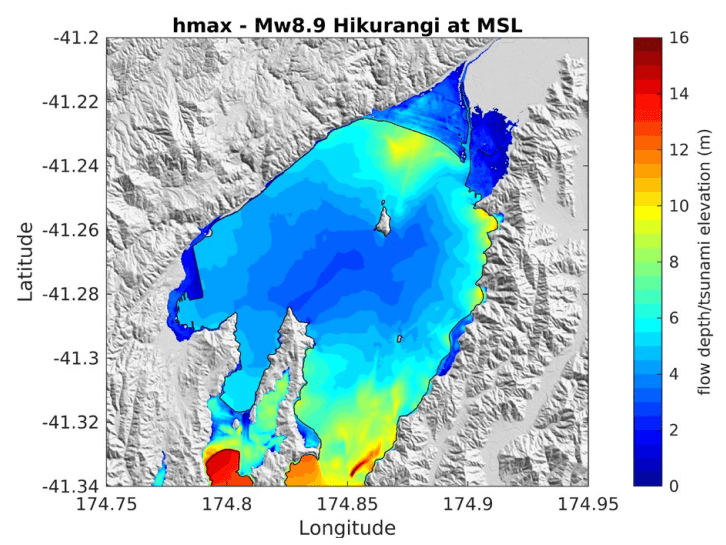

So, how can Wellingtonians know what to expect in the future? Much localised tsunami science has been done to better understand our risk and how to mitigate it. At a big picture level, New Zealand’s National Tsunami Hazard Model (NTHM) tells us that Wellington’s biggest tsunamis are infrequent (e.g., 8-10 metre heights at the coast on average every 2,500 years). That is good news of course, but presents a unique challenge: how do we remain prepared for them given they could happen at any time?

Another challenge highlighted by the NTHM is that Wellington’s biggest problems are very close. The Hikurangi subduction zone – the plate boundary fault capable of major earthquakes – is on our doorstep. In fact, our biggest tsunami sources are all local. Tsunamis coming from South America give us about 14 hours of warning, whereas tsunamis coming from Cook Strait take minutes to arrive.

What this means is simple. There will not be an official warning. The only warning will be natural signs – the earthquake itself or unusual roaring noises from the sea or water lowering further than low tide. Hence the long or strong: get gone message from civil defence.

So, what can we do? Experience from events like the Boxing Day tsunami in 2004 and the Tōhoku tsunami in 2011 tells us that self-evacuation is a powerful tool. Noticing the natural signs and evacuating inland without waiting for an official warning saved many lives in these events. Deaths in Wellington from a large Hikurangi subduction zone tsunami are estimated to be in the thousands if nobody evacuates. The more who evacuate, the fewer deaths.

Wellington residents who evacuated after the 2016 Kaikōura earthquake did the right thing. The city experienced long shaking. Luckily the tsunami wasn’t big. But this “trial run” showed up the bottlenecks, traffic jams, and lack of safe spaces in some areas when everyone evacuates at once. Think about improvements you could make – find out whether your house or office is safe to remain in, walk or cycle instead of driving if you can, have a plan B route in case main thoroughfares are congested, and, if possible, end up at a friend’s house or community emergency hub so you have shelter while you wait for the all clear. It could be many hours.

Yes, tsunamis are infrequent occurrences but practicing self-evacuation regularly may save your life. Sign up for ShakeOut so your earthquake and tsunami responses become second nature. Know your evacuation zones to save you heading to the top of Wainuiomata Hill or Mount Victoria – you don’t have to go that high! And think about who you could help, or who could help you, if you need support with self-evacuation.

A Wellington resident wrote of the 1855 tsunami, “The sea was greatly disturbed by the succession of shocks and, as its intrusion along the foreshore threatened our house, we scrambled up the back to Mulgrave Street, where the Cathedral now stands and found a number of people already assembled there.”3 But some people had to be encouraged to evacuate in 1855, “One family would certainly have been drowned had not some sailor…recognized the character of the approaching wave the moment it became visible.”4

Wellington anniversary weekend 1855 is an anniversary worth remembering. In the same way as marking the anniversaries of earthquakes focuses us on being prepared rather than scared, remembering tsunami anniversaries can help us be ready for their occasional occurrence. So, on this anniversary, how about turning your weekend walk or bike into a tsunami hīkoi with a refreshed grab bag and the company of whoever might need support to get to high ground? Conveniently, Wellington is not short of hills and many residents are adept at climbing them!

- As cited on p. 33 of Grapes, R. 2000. “Magnitude Eight Plus”. Victoria University Press, Wellington. ↩︎

- Withers 1901 as recorded in record 33 of the New Zealand Tsunami Database. ↩︎

- Matthews c. 1925 as recorded in record 33 of the New Zealand Tsunami Database. ↩︎

- Davie 1870 as cited in record 40 of the New Zealand Tsunami Database. ↩︎