The arrival of tsunami waves on Aotearoa’s shores from the magnitude 8.8 Kamchatka Earthquake last week brought with them a strange sense of comfort for me. They reminded me that we are connected across this Earth, with all its perils and beauty. They reminded me too that I’ve been lucky enough to learn tsunami science from their place of origin – the incredible Kamchatka Peninsula…

Brett Gillies was worried. He thought it was a bad idea. He was head of property at the Institute of Geological and Nuclear Sciences, but he also looked out for people, especially new, inexperienced ones.

Tsunami scientists Gaye Downes and Mauri McSaveney thought it was a great idea. As a New Zealand born and trained geologist, fresh out of a PhD, they thought overseas experience was exactly what I needed. And if the International Workshop on Local Tsunami Warning and Mitigation was being held in Far Eastern Russia that year, then that was where I needed to go.

It was 2002 and I had just started working at a New Zealand Crown Research Institute where I was tasked with looking for evidence of past large earthquakes and tsunamis from the Hikurangi Subduction Zone.

Travelling from Aotearoa to Russia to learn about earthquakes and tsunamis is not as far-fetched as it sounds – we have geological similarities. In remote eastern Russia, there’s a tongue of land that hangs down from the mainland and approaches the Pacific Plate. Along the southeastern margin of this Kamchatka Peninsula, the Pacific Plate is subducting – just as it does offshore of the North Island of New Zealand. The Kuril-Kamchatka Subduction Zone is much more active than our Hikurangi subduction zone – meaning more large earthquakes in shorter amounts of time – making it a great place to get insights into subduction zone earthquakes and tsunamis.

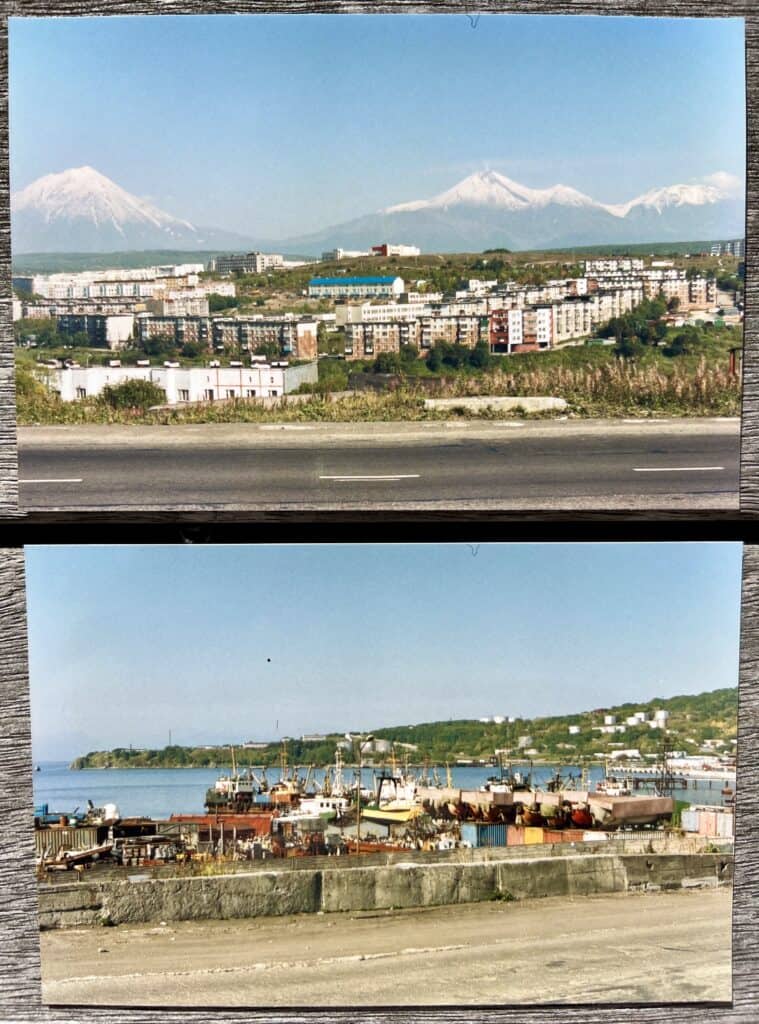

So that’s how I ended up at the airport in Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky, after the steepest descent in my flying history, faced with a formidable line-up of uniformed officials. Without more than a few words of Russian or a clue how to get through security, I followed the actions of a Japanese man who I guessed was another conference attendee. We both smiled with relief once we made it through the airport.

The town was daunting too. There was a lot of concrete; if there was any architectural aesthetic beyond function, it was brutalist; the hotel felt a bit like a cage. Walking some of the back-blocks, life here looked bleak, gritty, hard. But, as if to offset the hard exteriors, warmth flowed from the people as soon as there was a chance to interact. And the hospitality was generous and sincere.

Colourful spreads of food were laid out at every opportunity. One meal stands out. The cooking of ukha – a clear fish soup – over an open fire on the coastal plain during a fieldtrip, was something else. The smell of dill, nutritious chunks of fresh fish, warming root veges in a backdrop of super flavoursome broth. If I’m ever on the verge of forgetting about that meal, my keen fisherman husband will remind me of it. We have tried to replicate it but never achieved the uniquely Russian flavours I recall tasting that day – a true melding of food and environment. You had to be there.

Vodka was also prolific. I had been warned. And I was very pleased with my management of it – to start with. At the conference dinner, every country was welcomed with a toast, and every attendee was expected to down a shot of vodka at each toast. With twelve countries in attendance, I knew that was beyond my capabilities. I surreptitiously took a tiny sip to toast each country instead.

The conference was being held in Kamchatka to mark the 50th anniversary of the 1952 Great Kamchatka Earthquake. That was a devastating magnitude 9 earthquake and tsunami that initiated concerted study of tsunami hazard in Russia. That tsunami also reached New Zealand with reports of strong currents and raised water levels recorded in the New Zealand Tsunami Database. One person was injured when his fishing launch was carried under the bridge in the estuary at Matapouri Bay.

The conference was useful scientifically but, for me as a newbie, it was getting to know international tsunami scientists that was most valuable. Little did we know it then, but two years later we would need to come together as a global community to respond and learn from the deadliest tsunami ever – the 2004 Indian Ocean Tsunami. Repercussions from that event continue worldwide. For New Zealand, it initiated a review into what we knew about our own tsunami hazard and the risks tsunamis pose to this country – an ongoing process, the latest iteration of which is New Zealand’s National Tsunami Hazard Model.

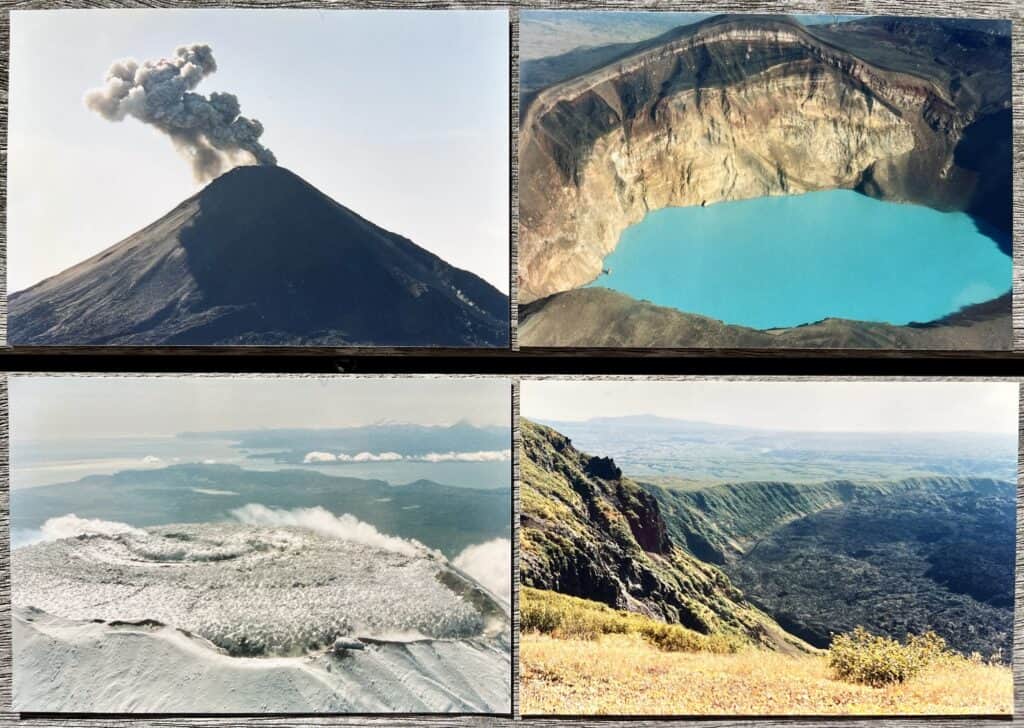

For geologists, Earth is our best teacher. And the conference fieldtrips enabled us to get out and see what makes Kamchatka phenomenal – the landscape. One fieldtrip was like a plate boundary lecture from the air. From an old Russian helicopter, we could look out to the Pacific Ocean and almost see the trench where the Pacific Plate was disappearing beneath the Okhotsk Plate. The edge of the land looked daring to be riding so close to such a fast-moving collision zone. Not far inland was a string of volcanoes, some proving their aliveness by erupting as we flew past. There are so many volcanos on Kamchatka (somewhere between 100 and 300), and in such a distinct line, that they must be part of the inspiration for the name ‘Pacific Ring of Fire’. We landed on a volcanic plateau, and a picnic lunch was laid out on the bench seats inside the helicopter. Some people swam in the turquoise, volcanic lake but the acidity levels were greater than my bravery and I was already over-stimulated by the stunning surroundings.

On the flight back to Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky, I got a bird’s eye view of bears fishing for salmon in a river. It’s one of the most surreal, beautiful and yet ordinary (the bears were just getting lunch) sights I’ve witnessed. With ‘little she-bear’ being the meaning of my name Ursula, this experience holds strongly in my memory. But the challenges of working in bear territory were also brought home to me. There was one conference attendee I’d been especially looking forward to meeting. She studied diatom microfossils like I did, and I was keen to compare notes. I couldn’t find her at the meeting, and I learned later that she’d been injured by a bear while doing fieldwork.

Bears were not a threat to me on this visit. As it turned out, it was vodka that nearly did me in. After my drinking success at the conference dinner, I let my guard down in the relaxing environment of dinner at a local’s house with a few tsunami scientists who I’d made friends with. After watching an old-fashioned slideshow of volcanic eruptions, it was me who encouraged everyone to have another shot of vodka at midnight to celebrate a colleague’s professorship. That was one shot too many for me and I spent the next day in bed recovering. I suspect the locals are accustomed to foreigners having to go through a vodka acclimatisation process. There was no loss of respect; in fact, there was generous knowledge sharing and invitations to join future field campaigns in Kamchatka. But for this cautious, born-and-bred kiwi, Fiordland (without bears) was my preferred remote fieldwork location.

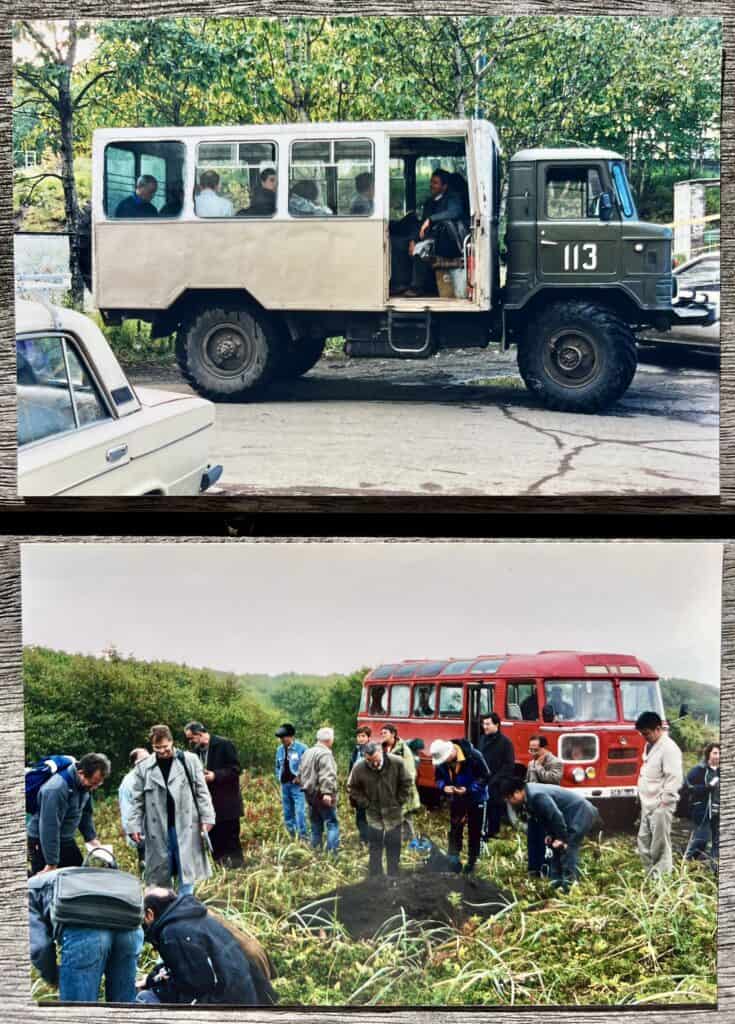

Another fieldtrip out towards the open coast from Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky involved visiting evidence of past tsunami events with Jody Bourgeois and Tanya Pinegina. With a quick pit dug in the ground, the tsunami layers revealed themselves – interfingered with volcanic ash layers that acted as time stamps. I was watching textbook examples come to life of exactly what I was meant to be looking for back in New Zealand. The geologists working in this part of the world were documenting evidence for large tsunamis (run-up heights of 6-10 metres) occurring every few decades back in time. No wonder they were easy to find! With much lower plate motion rates in New Zealand and higher sedimentation rates, it was going to be more like finding needles in a haystack.

Although we never found such stark, stripey layers back home, we did find evidence of subduction earthquakes and tsunamis. With detailed geological detective work by a small team over two decades (among many other projects), we now have a 7000-year history of events for the Hikurangi Subduction Zone. We know we can have earthquakes like the magnitude 8.8 Kamchatkan one here, and there will be a tsunami that comes with the next one. Thankfully, our events are much less frequent. In comparison to the Kuril-Kamchatka Subduction Zone, the Hikurangi Subduction Zone is like a kid sister trying to be a grown-up and failing.

I got a good hug from Brett Gillies on my return from Russia – he was relieved I was safely home. I hadn’t realised how worried he’d been. Yes, there had been all sorts of risks like vodka, bears, old helicopters, acid lakes, not to mention potential earthquakes and tsunamis, but I’d also had a trip that opened my eyes and still sits with me vividly and fondly over twenty years later. There are risks and rewards to plate boundary living!

The tsunami that accompanied Kamchatka’s magnitude 8.8 earthquake on 29th July 2025 will no doubt leave a thin layer of sediment on proximal shores of the peninsula and the ash now erupting from Klyuchevskoy volcano may well be the next sediment to cover the tsunami deposit – demonstrating in real time the evidence that geologists use to estimate hazard. These events are an excellent reminder that we can all be part of learning how the Earth works and living more wisely on it.